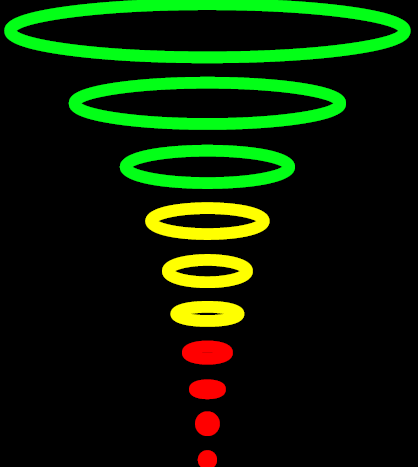

If you’ve ever wondered why eddy current testing (ECT) works the way it does — why the impedance plane looks like it does, why frequency matters, or how we predict the depth of penetration — you’re benefitting from the work of two independent giants:

Dr. Friedrich Förster in Germany. and Hugo Libby (with Richard Hochschild and A.L. Franklin) in the United States.

Together — intentionally or not — they created the dual foundations that the entire modern eddy current industry still stands on today.

This blog tells the story of how two different approaches evolved, where they intersect, and how their combined insights still drive today’s test methods, instruments, and training.

Förster: Ground Zero for Practical Eddy Current Theory

Dr. Friedrich Förster began developing electromagnetic testing methods in Germany in the late 1930s, at a time when:

-

ECT theory was not formalized

-

impedance-plane visualization did not exist

-

material characterization by induction was in its infancy

-

there were no standardized equations for depth of penetration or skin effect in NDT contexts

Förster had to build a conceptual and mathematical framework from scratch.

His approach centered around effective permeability (µ_eff) — not the literal material permeability, but the apparent permeability that accounts for:

-

true material µ_r

-

eddy current shielding

-

coil geometry

-

frequency

-

phase lag with depth

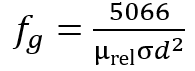

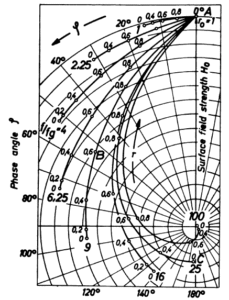

Förster paired µ_eff with his Limit Frequency concept — effectively his “secret sauce.” Limit Frequency was his method for predicting how changes in material properties (conductivity, permeability, hardness, case depth, etc.) would shift a coil’s impedance vector. Shown below are one of Dr. Förster’s Limit Frequency equations and one of his typical impedance graphs for predicting amplitude and phase angles

of field strength distribution within a metallic cylinder.

.

Using this system, he could:

-

predict phase and amplitude

-

categorize materials

-

assess heat treatment

-

sort to extraordinary precision

And it worked.

By the late 1950s, Förster’s instruments were inspecting more than 5 million parts per day across Europe, with sensitivity capable of measuring precise material properties in materials as small as 0.001 grams.

An astonishing achievement.

His approach was brilliant — but dense. The math was non-trivial, the concepts abstract, and the derivations tuned to his very specific coil geometries and instrument architecture.

But to understand how this knowledge reached the U.S., we need to introduce a key historical moment.

Hochschild’s 6-Month Mission to Förster’s Lab

Around 1957–1958, Richard Hochschild, sponsored by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, spent approximately six months at Förster’s laboratory in Reutlingen, Germany.

What resulted was a massive, detailed report — essentially a complete transmission of Förster’s concepts — which the AEC then distributed to U.S. research centers including:

-

Oak Ridge National Laboratory

-

Hanford Laboratories in Richland, WA

-

Argonne and other NBS (now NIST) partners

For the first time, American national labs had deep visibility into Förster’s analytical foundations.

And this raises the critical question:

Did Libby and Franklin Intentionally Break From Förster — or Did They Hit a Theoretical Wall?

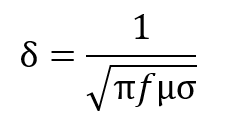

Shortly after Hochschild’s report circulated through the U.S., Hugo Libby and A.L. Franklin began publishing their own work: the now-famous Standard Depth of Penetration formula.

Their approach was notably different from Förster’s:

Förster:

-

Built a coil-centric, permeability-driven model

-

Focused on “effective permeability” and limit frequency

-

Relied on impedance-plane trajectory interpretation

Libby/Franklin:

-

Treated the material as layered current sheets

-

Derived depth of penetration directly from Maxwell’s equations

-

Produced a concise, general-purpose formula:

This formula was simple, elegant, and adaptable to virtually any probe or geometry.

So why the divergence?

Three possibilities — and all are probably correct:

1. Libby saw limitations in applying Förster’s approach broadly.

Förster’s limit frequency works beautifully for Förster coils, but becomes less accurate as:

-

coil sizes change

-

geometries change

-

materials become nonlinear

-

frequencies move outside intended regions

Libby’s δ formula is universal.

2. Libby wanted a model grounded in classical electromagnetic theory.

Limit Frequency is semi-empirical.

Libby’s formula is fully derived from Maxwell’s equations.

3. Libby made Förster’s concepts more usable for engineers and technicians.

Förster’s graphs are brilliant… but difficult to teach.

Libby distilled complex behavior into:

-

one formula

-

one graph

-

one intuitive physical explanation

This made ECT far more accessible for training, industry uptake, and standardization.

Does That Mean Förster Was Wrong? Absolutely Not.

If anything, Förster was decades ahead.

His µ_eff concept anticipated:

-

multi-frequency ECT

-

permeability sorting

-

case-depth analysis

-

magnetic saturation effects

-

complex impedance modeling

-

field penetration profiles

His “limit frequency” idea is essentially an early, analog precursor to the computational modeling done today by:

-

semi-analytical forward solvers

-

COMSOL and FEMM

-

Eddyfi’s Magnifi and ProbeScan modeling tools

-

In-house NDT research codes worldwide

If Förster had access to a modern GPU cluster, he would have built COMSOL 25 years early.

So Why Don’t We Use Förster’s Limit Frequency Today?

Because Libby’s formulation became:

-

simpler

-

more general

-

geometry-independent

-

easier to standardize

-

easier to teach

-

easier to embed in calculators and charts

Libby didn’t replace Förster — he translated Förster’s insights into a simpler, more universal language.

The Real Legacy: Förster + Libby = Modern Eddy Current NDT

Modern ECT is not “Förster OR Libby.”

It is absolutely both.

From Förster we inherited:

-

impedance-plane interpretation

-

permeability effects

-

frequency response understanding

-

complex induction models

-

coil-material coupling concepts

-

the practical art of sorting and heat treatment evaluation

From Libby/Franklin we inherited:

-

a universal formula for depth of penetration

-

modern flaw detection theory

-

frequency selection guidelines

-

textbook-ready explanations

-

the calculational framework used today

Today’s eddy current industry is the fusion of both approaches.

Every time you interpret a phase-angle response, thank Förster.

Every time you choose a frequency to hit 1–2 standard depths, thank Libby.

Conclusion: Two Different Ladders to the Same Rooftop

Förster built the first ladder from scratch — rung by rung — grounded in intuition, experimentation, and inductive reasoning.

Libby built a second ladder — grounded in mathematical rigor and standardization.

Both ladders reached the same rooftop.

And we’re still standing on it.

Want to Understand These Concepts Like a Level III?

eddycurrent.com is the only website in the world that combines:

-

historical papers

-

modern explanations

-

training videos

-

calculators

-

equipment comparisons

-

AI-powered interpretation help

-

and expert guidance from one of the leading authorities in the industry

If you want to truly master eddy current testing — the physics, the math, the history, and the practice — start here:

👉 Visit eddycurrent.com

👉 Subscribe for updates

👉 Explore the training section

Your journey into the real depth of eddy current testing starts now.